Known already in ancient times, first in Egypt and then in the Roman age, bead production also came from glass rods.

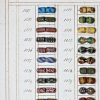

The first beads to be produced in Venice go back to the fourteenth century, and for centuries these were invaluable items in trade and exportation with Africa, the Americas and India. Depending on which technique is used for their production, Venetian beads can be either conteria (seed beads), rosetta (chevron beads) or a lume (lamp-worked beads). Documented in Murano as early as the fourteenth century, seed beads are monochrome, tiny and produced ‘industrially’ from thin hollow glass rods.

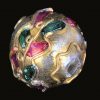

They can be also used for embroidery and different kinds of compositions. Invented in the fifteenth century by Marietta Barovier, Angelo’s daughter, chevron beads are made from hollow rods made of several multi-coloured layers like the murrine. Lamp-worked beads go back to the seventeenth century. These are made by heating a rod of solid glass over a naked flame (lume).

The molten glass drips onto a metal wire that is held in one hand and continually rotated, creating infinite variations, effects and colours with different additions. During the crisis afflicting Murano in the nineteenth century, bead production was the only one that flourished and actually managed to expand. On display here are some interesting and colourful set of samples from some of the most active producers including Franchini family and Domenico Bussolin, who also specialised in filigree.

However, the museum’s extensive collection offers an excursus into the history and the different kinds of Venetian beads, a genre that was of particular significance and closely linked to the city’s history and traditions; it played a special role in female employment, starting with Marietta Barovier’s own creativity, and many Murano women have always worked in this sector. Of particular note are the highly skilled Venetian bead threaders, impiraresse, who for centuries, with their box (sessola), full of beads on their knees would sit outdoors in the alleyways and little squares, and were a characteristic feature of a “vernacular” Venice that was full of people and life.